Model Selection with Large Neural Networks and Small Data

Highly overparameterized neural networks can display strong generalization performance, even on small datasets.

This is certainly a bold claim, and I suspect many of you are shaking your heads right now.

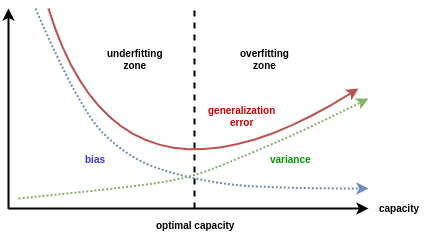

Under the classical teachings of statistical learning, this contradicts the well-known bias-variance tradeoff. This theory defines a sweet-spot where, if you increase model complexity further, generalization error tends to increase (the typical U-shaped test error curve).

You would think this effect is more pronounced for small datasets where the number of parameters, p, are larger than the number of observations, n, but this is not neccessarily the case.

In a recent ICML 2020 paper by Deepmind (Bornschein, 2020), it was shown that one can train on a smaller subset of the training data while maintaining generalizable results, even for large overparameterized models. If this is true, we can reduce the computational overhead in model selection and hyperparmater tuning significantly.

Think for a moment regarding the implications of this. This could dramatically alter how we select optimal models or tune hyperparameters (for example in Kaggle competitions), since we can include significantly more models in our grid search (or the like).

Is this too good to be true? And how can we prove it?

Here are the main takeaways before we get started:

- Model selection is possible using only a subset of your training data, thus saving computational resources (relative ranking-hypothesis)

- Large overparameterized neural networks can generalize surprisingly well (double descent)

- After reaching a minimum, test cross-entropy tends to gradually increase over time while test accuracy improves (overconfidence). This can be avoided using temperature scaling.

Let’s get started.

1. Review of classical theory on the bias-variance trade-off

Before we get started, I will offer you two options. If you are tired of hearing about the bias-variance trade-off for the 100th time, please read the TLDR at the end of this Section 1 and then move on to Section 2. Otherwise, I will briefly introduce the bare minimum needed to understand the basics before moving on with the actual paper.

The predictive error for all supervised learning algorithms can be broken into three (theoretical) parts, which are essential to understand the bias-variance tradeoff. These are; 1) Bias 2) Variance 3) Irreducible error (or noise term)

The irreducible error (sometimes called noise) is a term disconnected from the chosen model which can never be reduced. It is an aspect of the data arising due an imperfect framing of the problem, meaning we will never be able to capture the true relationship of the data - no matter how good our model is.

The bias term is generally what people think of when they refer to model (predictive) errors. In short, it measures the difference between the “average” model prediction and the ground truth. Average might seem strange in this case as we typically only train one model. Think of it this way. Due to small pertubations (randomness) in our data, we can get slightly different predictions even with the same model. By averaging the range of predictions we get due to these pertubations, we obtain the bias term. High bias is a sign of poor model fit (underfitting), as it will have a large prediction error on both the training and test set.

Finally, the variance term refers to the variability of the model prediction for a given data point. It might sound similar, but the key difference lies in the “average” versus “data point”. High variance implies high generalization error. For example, while a model might be relatively accurate on the training set, it can achieve a considerably poor fit on the test set. This latter scenario (high variance, low bias) is typically the most likely when training overparameterized neural networks, i.e., what we refer to as overfitting.

The practical implication of these terms implies balancing the bias and variance (hence the name trade-off), typically controlled via model complexity. The ultimate goal is to obtain low bias and low variance. This is the typical U-shape test error curve you might have seen before.

.

.

Alright, I will assume you know enough about the bias-variance trade-off for now to understand why the original claim that overparameterized neural networks do not ncessarily imply high variance is puzzling, indeed.

TLDR; high variance, low bias is a sign of overfitting. Overfitting happens when a model achieves high accuracy on the training set but low accuracy on the test set. This typically happens for overparameterized neural networks.

2. Modern Regime - Largers models are better!

In practice, we typically optimize the bias-variance trade-off using a validation set with (for example) early stopping. Interestingly, this approach might be completely wrong. Over the past few years, researchers have found that if you keep fitting increasingly flexible models, you obtain what is termed double descent, i.e., generalization error will start to decrease again after reaching an intermediary peak. This finding is empirically validated in Nakkiran et al. (2019) for modern neural network architectures on established and challenging datasets. See the following figure from OpenAI, which shows this scenario;

- Test error initially declines until it reaches a (local) minimum, and then starts increasing again with increasing complexity. In the critical regime, it is important that we keep adding model complexity, as the test error will start to decline again, eventually reaching a (global) minimum.

These findings imply that larger models are generally better due to the double descent phenomena, which challenges the long-held viewpoint regarding overfitting for overparamterized neural networks.

3. Relative Ranking-Hypothesis

Having established that large overparameterized neural networks can generalize well, we want to take it one step further. Enter the relative ranking hypothesis. Before we explain the hypothesis, we note that if proven true, then you can potentially perform model selection and hyperparameter tuning on a small subset of your training dataset for your next experiment, and by doing so save computational resources and valuable training time.

We will briefly introduce the hypothesis followed by a few experiments to validate the claim. As an additional experiment not included in the literature (as far as we know), we will investigate one setting that could potentially invalidate the relative ranking hypothesis, which is imbalanced datasets.

a) Theory

One of the key hypothesis of Bornschein (2020) is; “overparameterized model architectures seem to maintain their relative ranking in terms of generalization performance, when trained on arbitrarily small subsets of the training set”.

They call this observation the relative ranking-hypothesis.

In layman terms; let’s say we have 10 models to choose from, numbered from 1 to 10. We train our models on a 10% subset of the training data, and find that model 6 is the best, followed by 4, then 3, and so on..

The ranking hypothesis postulates, that as we gradually increase the subset percentage from 10% all the way up to 100%, we should obtain the exact same ordering of optimal models.

If this hypothesis is true, we can essentially perform model selection on a small subset of the original data to the added benefit of much faster convergence. If this was not controversial enough, the authors even take it one step further as they found some experiments where training on small datasets led to more robust model selection (less variance), which certainly seem counterintuitive given that we would expect relatively more noise for smaller datasets.

b) Temperature calibration

One strange phenomenom when training neural network classifiers is, that cross entropy error tends to increase while classification error decreases. This seems counterintuitive, but is simply due to models becoming overconfident in their predictions (Guo et al. (2017)). We can use something called temperature scaling, which calibrates the cross entropy estimates on a small held-out dataset. This yields more generalizeable and well-behaved results compared to classical cross-entropy, especially relevant for overparameterized neural networks. As a rough analogy, you can think of this as providing less “false negatives” regarding the number of overfitting cases.

While Bornschein (2020) do not provide explicit details on the exact softmax temperature calibration procedure used in their paper, we use the following procedure for our experiments;

- We define a held-out calibration dataset, C, equivalent to 10% of the training data.

-

We initialize the temperature scalar to be 1.5 (like in Guo et al. (2017))

-

For each epoch; 1) Calculate cross-entropy loss on our calibration set C 2) Optimize the temperature scalar using gradient descent on the calibration set (see this Github repo by Guo et al. (2017)) 3) Use the updated temperature scalar to calibrate the regular cross entropy during gradient descent

- After training for 50 epochs, we calculate the calibrated test error, which should no longer show signs of overconfidence.

Let us now turn to the experimental setting.

3. Experiments

We will conduct two experiments in this post. One for validating the relative ranking-hypothesis on the MNIST dataset, and one for evaluating how our conclusions change if we synthetically make MNIST imbalanced. This latter experiment is not included in the Bornschein (2020) paper, and could potentially invalidate the relative ranking-hypothesis for imbalanced datasets.

MNIST

We start by replicating the Bornschein (2020) study on MNIST, before moving on with the imbalanced dataset experiment. This is not meant to disprove any of the claims in the paper, but simply to ensure we have replicated their experimental setup as closely as possible (with some modifications).

- Split of 90%/10% for the training and calibration sets, respectively

- Random sampling (as balanced subset sampling did not provide any added benefit according to the paper)

- 50 epochs

- Adam with fixed learning rate [10e-4]

- Batch size = 256

- Fully connected MLPs with 3 hidden layers and 2048 units each

- Without dropout (made our results too unstable to include)

- A simple convolutional network with 4 layers, 5x5 spatial kernel, stride 1 and 256 channels

- Logistic regression

- 10 different seeds to visualize uncertainty bands (30 in original paper)

The authors also mention experimenting with replacing ReLU with tanh, batch-norm, layer-norm etc., but it is unclear if these tests were included in their final results. Thus, we only consider the experiment using the above settings.

Experiment 1: How does temperature scaling during gradient descent affect generalization?

As an initial experiment, we want to validate why temperature scaling is needed. For this, we train an MLP using ReLU and 3 hidden layers of 2048 units each, respectively. We do not include dropout and we train for 50 epochs.

Our hypothesis is: The test cross entropy should gradually increase while test accuracy decreases over time (motivation for temperature scaling in the first place, i.e., model overconfidence).

Here are the results from this initial experiment:

Clearly, the test entropy does decline initially and then gradually increase over time while test accuracy keeps improving. This is evidence in favor of hypothesis 1. Figure 3 in Guo et al. (2017) demonstrates the exact same effect on CIFAR-100.

Clearly, the test entropy does decline initially and then gradually increase over time while test accuracy keeps improving. This is evidence in favor of hypothesis 1. Figure 3 in Guo et al. (2017) demonstrates the exact same effect on CIFAR-100.

Note: We have smoothed the results a bit (5-window rolling mean) to make the effect more visible.

Conclusions from Experiment 1:

- If we keep training large neural networks for sufficiently long, we start to see overconfident probabilistic predictions, making them less useful out-of-sample.

To remedy this effect, we can incorporate temperature scaling which a) ensures probabilistic forecasts are more stable and reliable out-of-sample and b) improves generalization by scaling training cross entropy during gradient descent.

Balanced Dataset

Having shown that temperature scaling is needed, we now turn to the primary experiment - i.e., how does test cross-entropy vary as a function of the size of our training dataset. Our results look as follows:

Interestingly, we do not obtain the exact same “smooth” results as Bornschein (2020). This is most likely due to the fact, that we have not replicated their experiment completely, as they for example include many more different seeds. Nevertheless, we can draw the following conclusions:

- Interestingly, the relatively large ResNet-18 model does not overfit more than logistic regression at any point during training!

- The relative ranking-hypothesis is confirmed

- Beyond 25000 observations (roughly half of the MNIST train dataset), the significantly larger ResNet model is only marginally better than the relatively faster MLP model.

Imbalanced Dataset

We will now conduct an experiment for the case of imbalanced datasets, which is not included in the actual paper, as it could be a setting where the tested hypothesis is invalid.

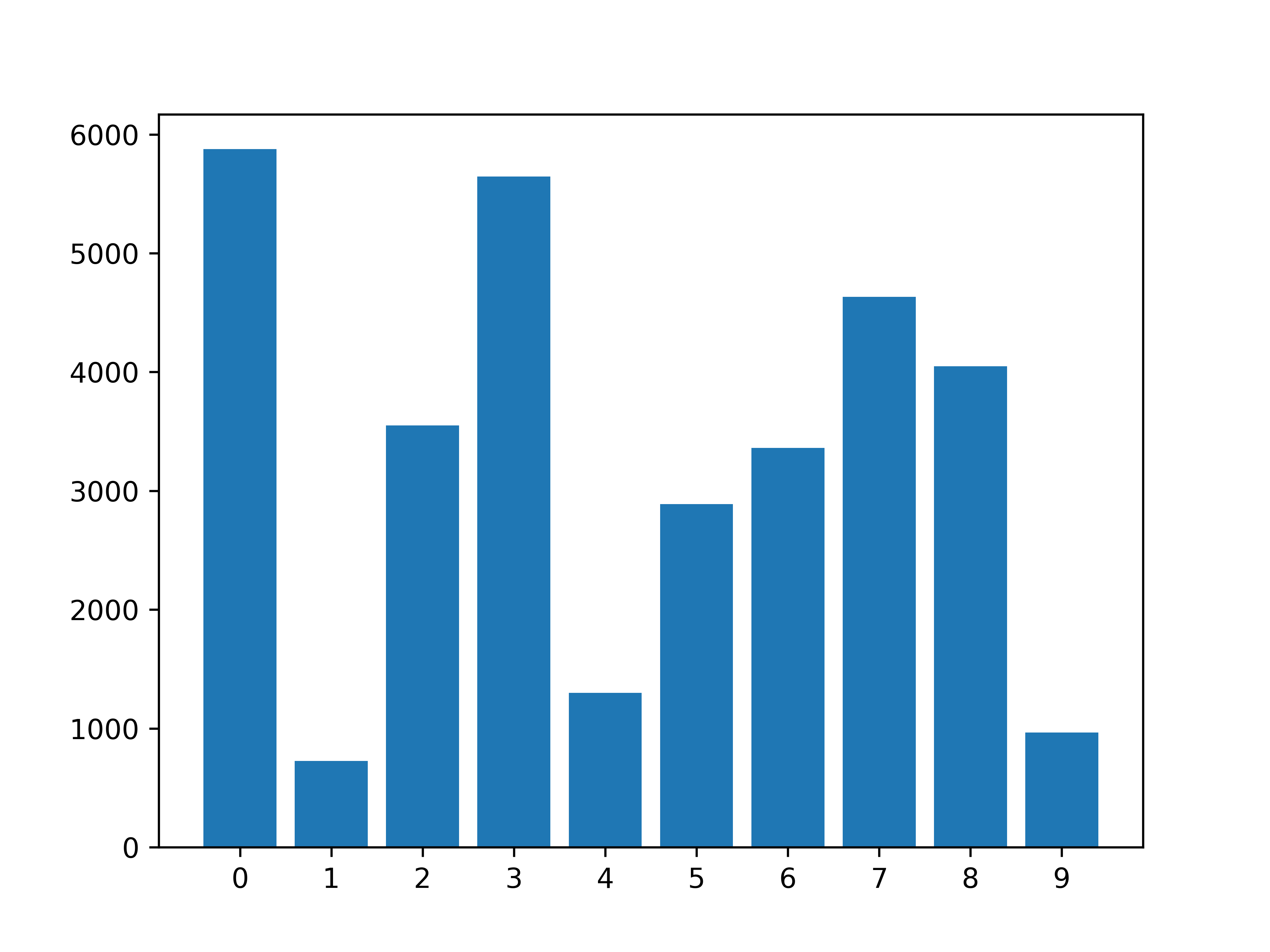

We sample an artificially imbalanced version of MNIST similar to Guo et al. (2019). The procedure is as follows. For each class in our dataset, we subsample between 0 and 100 percent of the original training and test dataset. We use the following github repo for this sampling procedure. Then, we select our calibration dataset similar to the previous experiment, i.e., random 90/10% split between training and calibration.

We include a visualization of the classes distribution for the original MNIST training dataset

and the imbalanced version

Given this large difference in frequency distribution, you can clearly see how this version is much more imbalanced compared to the original MNIST.

While a plethora of different methods for overcoming the problem of imbalanced datasets exists (see the following review paper), we want to investigate and isolate the effects of having an imbalanced dataset for the relative ranking hypothesis, i.e., does the relative ranking-hypothesis still hold in the imbalanced data setting?

We run all our models again using this synthetically imbalanced MNIST dataset, and obtain the following results:

So has the conclusion changed?

Not really!

This is quite an optimistic result, as we are now more confident, that the relative ranking-hypothesis is mostly true in the case of imbalanced datasets. We believe this could also be the reason behind the quote from the Bornschein (2020) paper regarding the sampling strategy; “We experimented with balanced subset sampling, i.e. ensuring that all subsets always contain an equal number of examples per class. But we did not observe any reliable improvements from doing so and therefore reverted to a simple i.i.d sampling strategy.”

The primary difference between the balanced and imbalanced results is the more “jumpy” results, which makes sense given that there might be classes available in the test set not seen during training for the chosen models.

4. Summary

To sum up our findings:

- Due to the relative ranking-hypothesis, we can perform model selection using only a subset of our training data for both balanced and imbalanced datasets, thus saving computational resources

- Large overparameterized neural networks can generalize surprisingly well, even on small datasets (double descent)

- We can avoid overconfidence by applying temperature scaling

I hope that you might be able to apply these findings in your next machine learning experiments, and remember, larger is (almost) always better.

Thank you for reading!

5. References

[1] J. Bornschein, F. Visin, and S. Osindero, Small Data, Big Decisions: Model Selection in the Small-Data Regime (2020), in International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

[2] P. Nakkiran, G. Kaplun, Y. Yang, B. T. Barak and I. Sutskever, Deep double descent: Where bigger models and more data hurt (2019), arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.02292.

[3] C. Guo, G. Pleiss, Y. Sun, and K. Q. Weinberger, Guo, C., Pleiss, G., Sun, Y., & Weinberger, K. Q. (2017). On calibration of modern neural networks (2017), arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.04599.

[4] T. Guo, X. Zhu, Y. Wang, and F. Chen, Discriminative Sample Generation for Deep Imbalanced Learning (2019), in International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization (IJCAI) (pp. 2406-2412).